For a guy who lives a secular life, it seems to be quite a preoccupation with tracking the major religious observances--even of the Jewish kind. Maybe I need a therapy of sorts to bring out my inner, repressed, religiosity. And then maybe I, too, will become a "sadhguru" but without having killed anyone. Nah! ;)

There was one thing about Deepavali that was heavenly for me--the sweets that my mother made. When we were kids, my brother and I were hell bent on figuring out where mother had hid the Deepavali sweets from our greedy eyes and mouths. We always succeeded, and enjoyed the sneak-previews of the delights that awaited.

My favorite was the phenomenally awesome sweet that mother made with cashews. And, those days, it was pretty much home-grown cashews--most of the nuts came from the tree within our compound. I could--and did--eat them all day long.

But then, somewhere in my growing up, I became duller and more boring than I have always been. I became the party-pooper. The killjoy. Major Buzzkill. "No, thanks" became my middle name, and my consumption of sweets dropped! ;)

The more I live and learn, the more I am thankful that such an attitude change happened, and that I became sweet- and food-conscious. Else, there is a fair chance that I would have become a part of the ever growing reports on obesity and diabetes.

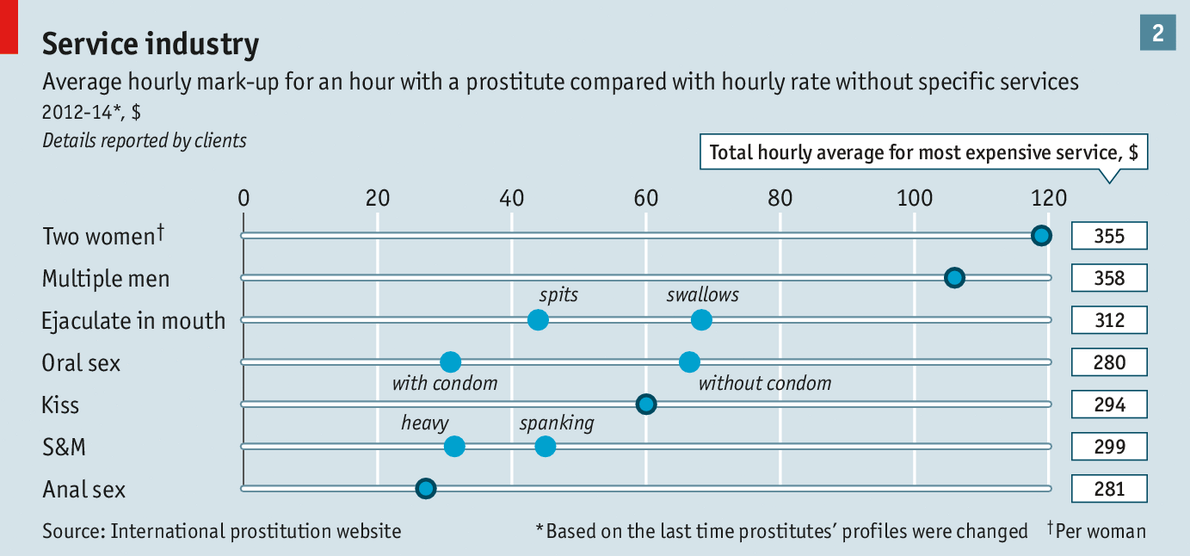

Sugar is a major cause of this pubic health issue. Not only in the United States but all over the world. Sugar in the traditional sweets, which one can buy every single day, unlike the rarity of the old days. And, sugar is seemingly an additive in everything that we eat and drink. Which is why the evil industry is trying to get more sugar into baby foods too. Bastards these companies are, yet again demonstrating that market and morals rarely ever intersect! Like this:

A yogurt-based Happy Baby snack for children contains a teaspoon of sugar per serving, with four servings per pouch. Happy Tot’s organic bananas and carrots fiber and protein bar contains 2 teaspoons of sugar per serving.In order to truly understand the seriousness of this, go to the kitchen and measure out 2 teaspoons of sugar. That itself will shock you. And then put all that sugar in your mouth, and imagine what that might do if a 2-year old were given that much sugar.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that nearly 14 percent of 2- to 5-year-olds are obese (above the 95th percentile for body mass index), a percentage that is higher for African Americans, Hispanics and low-income Americans. A new study says that in the United States, childhood obesity alone is estimated to cost $14 billion annually in direct health expenses.If your defense at this point is that parents should know better, and that we should not blame the industry, it means that you are a big part of the problem.

|

| Caption at the source: A milk-based "toddler drink" contains 3 1/2 teaspoons of sugar per serving. (Bill O'Leary/The Washington Post) |