It was supposed to be the scariest evening of the year: Halloween.

It was anything but.

Treats everywhere.

The air was cool and moist when I stepped out for my favorite walk by the favorite river. The sky was gloriously colorful.

I came home refreshed, recharged, and renewed.

I wanted to read a poem that would fit the mood. The cosmos answered in the form of a Google answer. The title of this post is borrowed from that poem:

To the Reader: Twilight

By Chase Twichell

Whenever I look

out at the snowy

mountains at this hour

and speak directly

into the ear of the sky,

it’s you I’m thinking of.

You’re like the spirits

the children invent

to inhabit the stuffed horse

and the doll.

I don’t know who hears me.

I don’t know who speaks

when the horse speaks.

Since 2001 ........... Remade in June 2008 ........... Latest version since January 2022

Friday, October 31, 2014

Thursday, October 30, 2014

I find out that I am ... "bourgeois trash"

The academic world is a strange place.

Yes, that was an understatement. But, I am trying to be polite here ;)

A couple of days ago, I was in my office, reading and writing as I always end up doing. After all, in my life as an exile, it is not as if busloads of students and faculty come to chat with me, right?

I heard two colleagues conversing in the hallway, and quite loudly too. From their voices, I knew who they were and didn't even have to peek out.

The louder of the two was complaining about some faculty colleague, who is not a member of the union. Apparently this non-member had raised some questions regarding the use of "fair share" money for political activities. I knew it couldn't be me--it has been years since I commented on anything, after I was told to "please shut up."

Anyway, this was when the louder voice got even louder: "that bourgeois trash has no idea how we do things" he yelled.

Such name calling does not surprise me anymore. In the academic world, it has practically become the standard operating procedure not to debate ideas but to instead engage in ad hominem attacks.

And then the louder voice remarked to the other person: "you have one close to home too." The other voice now mumbled something and the two immediately lowered their decibels.

Guess who was being referred to as the one close to home? Yep, moi.

Which means, I am also "bourgeois trash."

Why academics shy away from intellectual debates baffles me to no end. After all these years I should not be surprised, yes. But, I cannot help it but be surprised at the virulent anti-intellectual atmosphere at a place that the rest of the world would think it is all about intellectual discussions!

I was thinking about this and walking towards the campus health center to get my flu shot. I suppose I was so deep in my thoughts that I didn't even hear a colleague calling for my attention. The driver of the car honked to get my attention.

"You are not supposed to walk in front of oncoming cars" she joked.

In the conversation that followed, she lamented about the anti-intellectual college environment. "It is like what my friend says--the church is the best place these days to hide from god."

This atheist is now convinced that god is also my kind of people: "bourgeois trash" ;)

Yes, that was an understatement. But, I am trying to be polite here ;)

A couple of days ago, I was in my office, reading and writing as I always end up doing. After all, in my life as an exile, it is not as if busloads of students and faculty come to chat with me, right?

I heard two colleagues conversing in the hallway, and quite loudly too. From their voices, I knew who they were and didn't even have to peek out.

The louder of the two was complaining about some faculty colleague, who is not a member of the union. Apparently this non-member had raised some questions regarding the use of "fair share" money for political activities. I knew it couldn't be me--it has been years since I commented on anything, after I was told to "please shut up."

Anyway, this was when the louder voice got even louder: "that bourgeois trash has no idea how we do things" he yelled.

Such name calling does not surprise me anymore. In the academic world, it has practically become the standard operating procedure not to debate ideas but to instead engage in ad hominem attacks.

And then the louder voice remarked to the other person: "you have one close to home too." The other voice now mumbled something and the two immediately lowered their decibels.

Guess who was being referred to as the one close to home? Yep, moi.

Which means, I am also "bourgeois trash."

Why academics shy away from intellectual debates baffles me to no end. After all these years I should not be surprised, yes. But, I cannot help it but be surprised at the virulent anti-intellectual atmosphere at a place that the rest of the world would think it is all about intellectual discussions!

I was thinking about this and walking towards the campus health center to get my flu shot. I suppose I was so deep in my thoughts that I didn't even hear a colleague calling for my attention. The driver of the car honked to get my attention.

"You are not supposed to walk in front of oncoming cars" she joked.

In the conversation that followed, she lamented about the anti-intellectual college environment. "It is like what my friend says--the church is the best place these days to hide from god."

This atheist is now convinced that god is also my kind of people: "bourgeois trash" ;)

Wednesday, October 29, 2014

A kiss is just a kiss ... unless it is in the land of the RSS

Growing up in a traditional Tamil Brahmin family, I easily gravitated to the classical music that was the cultural lifeblood in the immediate and extended families. A favorite of mine was a Bharatiyar poem set to music in the classical style, and the following lines when talented musicians would get into a jam session, as we might refer to it:

கன்னத்தில் முத்தமிட்டால்-உள்ளந்தான் கள்வெறி கொள்ளுதடீ

உன்னை தழுவிடிலோ- கண்ணம்மா உன்மத்த மாகுதடீ.

In this movie clip, that verse is when the male voice kicks in (at 2:25)

Those lines are about how the lover's heart feels intoxicated with a kiss, and about an embrace that is sensual.

The strangest aspect was this: as a kid, I had never seen in real life lovers kissing or passionately embracing. Yet, here were these lyrics by Bharatiyar, who was a Tamil Brahmin himself, and whose hometown was not far from my grandmothers'. There was no kissing in the public, or anything even remotely passionate an embrace, not only among the Tamil Brahmins but pretty much by anybody. Those days, movies did not show kissing either.

To think that in my young days in the old country I had missed out on all the kissing and embracing, and the getting to first and second base that is all the norm for American teenagers!!! What a loss! ;)

Kissing is in the news in India. For the wrong reasons though:

While the initial trigger--the attack in the coffee shop--was led by Hindu activists, the "Kiss of Love" is opposed by the Muslim moral police too!

Of course, it being the India where there are taboos in plenty against young men and women socializing, it should not surprise anybody that:

கன்னத்தில் முத்தமிட்டால்-உள்ளந்தான் கள்வெறி கொள்ளுதடீ

உன்னை தழுவிடிலோ- கண்ணம்மா உன்மத்த மாகுதடீ.

In this movie clip, that verse is when the male voice kicks in (at 2:25)

Those lines are about how the lover's heart feels intoxicated with a kiss, and about an embrace that is sensual.

The strangest aspect was this: as a kid, I had never seen in real life lovers kissing or passionately embracing. Yet, here were these lyrics by Bharatiyar, who was a Tamil Brahmin himself, and whose hometown was not far from my grandmothers'. There was no kissing in the public, or anything even remotely passionate an embrace, not only among the Tamil Brahmins but pretty much by anybody. Those days, movies did not show kissing either.

To think that in my young days in the old country I had missed out on all the kissing and embracing, and the getting to first and second base that is all the norm for American teenagers!!! What a loss! ;)

Kissing is in the news in India. For the wrong reasons though:

To assert their right to love following an attack at a coffee shop in Kerala's Kozhikode district last week by the BJP activists, a group of youngsters in Kochi have decided to observe the next Sunday as 'Kiss Day'.Yep, when a religious-nationalist is elected to power, then moral policing automatically follows. To fight back, they have come up with a wonderful idea:

The event named Kiss of Love has been organised by a group of youngsters and invites everyone, old and young, to gather at the Marine Drive on Sunday evening and express their love in public. There is an air of excitement in the city and the social media is awash with youngsters confirming their participation. More than 2,500 people have registered for the event, while the likes have crossed 7000 and going up, something which even the organisers never expected.

While the initial trigger--the attack in the coffee shop--was led by Hindu activists, the "Kiss of Love" is opposed by the Muslim moral police too!

The "kiss of love" protest has been opposed by both hardline Hindu and Muslim groups in Kerala who say the event is against Indian culture.Yep, the kissing version of Bootleggers and Baptists!

Of course, it being the India where there are taboos in plenty against young men and women socializing, it should not surprise anybody that:

Many others on the net, boys and girls included, have expressed their willingness and excitement to take part in the event, but alas they are without partners.The old country is beyond anybody's understanding.

Cocktails and tears

"Is this shuttle bus going to Gate 44H?" the forty-ish blonde asked with a tone of panic. It is not that she didn't have reasons to panic. American airports are going from worst to worstest ever and asking customer service folks for clarification will only make one panic even more.

The younger man standing next to me assured her that we were all headed to the same place.

"Are you also going to Phoenix?" she now asked.

"No, to Eugene."

"Hey, I am also going to Eugene" I joined in as the bus jolted to a start.

"Oh, Eugene is a fun city" the blonde said loudly to make sure the bus noise did not drown her out. "More than twenty years ago, I went there when I was a teenager. The Grateful Dead were performing and my friends were going. I asked my mother to pay for my airplane ticket. From Montana, which is where I was then."

Ah, yes, the Deadheads. In Eugene. Tie-dye, and all. Made for each other.

"My mother bought me a one-way ticket. I reached Eugene with a twenty dollar bill. It was before cellphones."

By now she had moved closer to us and I got a strong whiff of alcohol breath. The shuttle reached Gate 44 and I was separated from Ms. Cocktails.

At my gate, a young woman, perhaps edging close to twenty, was sobbing away while trying to get a few words across to whoever she was talking with on her iPhone. A torture the separation from a loved one is when young. The world seems to come to an end. Even this old curmudgeon can easily recall those old teenage days.

It was time to board. No hurry.

As she passed me, the sobbing young woman was now only silently weeping and drying her eyes with tissue in her hand.

I was the last one to board.

As I reached my seat, it was Ms. Tears next to me.

I sat down. I reached for my seat belt and saw that she was looking in my direction.

"Are you ok?"

She nodded her head.

"I noticed you crying in the terminal ... I just want to make sure you are alright."

"Thanks. I am just having a tough time saying bye to a dear friend."

"Let me know if you think I can be of help" I said as I reached for the copy of The Atlantic that I had saved for this leg of the travel.

I imagined a young Ms. Cocktails twenty years ago sobbing away, and her mother spending her hard-earned money to pay for the daughter's airfare. In my mind, I wished Ms. Tears a life of happily ever after.

The younger man standing next to me assured her that we were all headed to the same place.

"Are you also going to Phoenix?" she now asked.

"No, to Eugene."

"Hey, I am also going to Eugene" I joined in as the bus jolted to a start.

"Oh, Eugene is a fun city" the blonde said loudly to make sure the bus noise did not drown her out. "More than twenty years ago, I went there when I was a teenager. The Grateful Dead were performing and my friends were going. I asked my mother to pay for my airplane ticket. From Montana, which is where I was then."

Ah, yes, the Deadheads. In Eugene. Tie-dye, and all. Made for each other.

"My mother bought me a one-way ticket. I reached Eugene with a twenty dollar bill. It was before cellphones."

By now she had moved closer to us and I got a strong whiff of alcohol breath. The shuttle reached Gate 44 and I was separated from Ms. Cocktails.

At my gate, a young woman, perhaps edging close to twenty, was sobbing away while trying to get a few words across to whoever she was talking with on her iPhone. A torture the separation from a loved one is when young. The world seems to come to an end. Even this old curmudgeon can easily recall those old teenage days.

It was time to board. No hurry.

As she passed me, the sobbing young woman was now only silently weeping and drying her eyes with tissue in her hand.

I was the last one to board.

As I reached my seat, it was Ms. Tears next to me.

I sat down. I reached for my seat belt and saw that she was looking in my direction.

"Are you ok?"

She nodded her head.

"I noticed you crying in the terminal ... I just want to make sure you are alright."

"Thanks. I am just having a tough time saying bye to a dear friend."

"Let me know if you think I can be of help" I said as I reached for the copy of The Atlantic that I had saved for this leg of the travel.

I imagined a young Ms. Cocktails twenty years ago sobbing away, and her mother spending her hard-earned money to pay for the daughter's airfare. In my mind, I wished Ms. Tears a life of happily ever after.

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

Are academic deans furious and waxing wroth over the latest athletic scandal?

The athletics-driven higher education is finally in some serious shit.

Way past time.

But at least now.

What happened, you ask?

Way past time.

But at least now.

What happened, you ask?

For 18 years, thousands of students at the prestigious University of North Carolina took fake "paper classes," and advisers funneled athletes into the program to keep them eligible, according to a scathing independent report released Wednesday. ...If ever one needed a metaphorical smoking gun in order to take the issue seriously, well, now there is no denying it.

In all, the report estimates, at least 3,100 students took the paper classes, but the figure "very likely falls far short of the true number."

"As an athlete, we weren't really there for an education," Rashad McCants, the second-leading scorer on the championship University of North Carolina basketball team 10 years ago, told CNN's Carol Costello. "You get a scholarship to the university to play basketball," he said. In other words, the point wasn't for him to actually learn. That's just sad.

"The university makes money off us athletes," McCants told Costello, "and they give us this fake education as a distraction." When McCants first made these remarks, university representatives tried to shoot the messenger, attacking him and his credibility.

Remember the lawsuits against the NCAA that colleges and the sports body were simply making money off the students who were hired under the guise of "student-athletes" but were, ahem, not students and only athletes? The whole thing is a "subversion of the academy":

The NCAA is a cartel of the major athletic universities in the United States that sets wages, playing conditions, and other aspects of intercollegiate athletics. Most prominently of these is a restriction on payments to football and basketball players. These two sports create billions of dollars in local and national revenues via gate receipts, TV contracts, and ancillary merchandise, not to mention millions of dollars annually at member schools in donations by alumni and other supporters of athletic programs.

It is a tangled web that was woven at UNC. A web that involved even a, wait for it, ethics professor! Yep, an ethics professor, who "directed the university’s Parr Center for Ethics," was totally in the middle of this scandal!

The president of Macalaster College is furious:

this is not fundamentally an issue about sports but about the basic academic integrity of an institution. Any accrediting agency that would overlook a violation of this magnitude would both delegitimize itself and appear hopelessly hypocritical if it attempted, now or in the future, to threaten or sanction institutions—generally those with much less wealth and influence—for violations much smaller in scale.

Most of us work very hard to conform to the standards imposed by our regional accrediting agencies and the federal government. If falsified grades and transcripts for more than 3,000 students over more than a decade are viewed as anything other than an egregious violation of those standards, my response to the whole accreditation process is simple: Why bother?

Exactly! Why bother with real work? I agree with him that the university should lose its accreditation until it is able to convince us that the grades mean something.

The crime involves fundamental academic integrity. The response, regardless of the visibility or reputation or wealth of the institution, should be to suspend accredited status until there is evidence that an appropriate level of integrity is both culturally and structurally in place.

Anything less would be dismissive of the many institutions whose transcripts actually have meaning.

Of course, that will not happen. Because, dammit, that won't happen! After all, this ain't anything new :(

Monday, October 27, 2014

Economy in the time of Ebola: An embargo!

I suppose the uber-religious who see a divine explanation in everything that happens might have a solid rationale for the Ebola nightmare in West Africa. Or, for that matter, even for slavery. But, for the rest of us rational people, we are worried that this latest outbreak of Ebola, which could have been easily contained if only the rest of the world had cared at least a tad, will set back economic conditions not only in the three primarily affected countries but in the rest of the continent too.

It will affect the entire continent because to most people in the world Africa is one country. One big blob. Ebola in Liberia becomes an "African" disease. An "African" problem. Thus, even as slowly the world is beginning to respond to the crisis, the irrational fear is driving individuals and businesses away from the sub-Saharan economy, in particular.

I suppose that it is only a continuation of history when we rich folks in the rich and poor countries decide that all we want to do is to lift up the drawbridges and keep the poor and the hungry and the ill away and on the other side of the moat, and casually remark that they can eat cakes. Some fucked up humans we are!

Have you made your donation to help those fight the good fight? I recommend donating to Doctors Without Borders.

It will affect the entire continent because to most people in the world Africa is one country. One big blob. Ebola in Liberia becomes an "African" disease. An "African" problem. Thus, even as slowly the world is beginning to respond to the crisis, the irrational fear is driving individuals and businesses away from the sub-Saharan economy, in particular.

"Everybody is running away from Ebola, Kaifala Marah [Sierra Leone's finance minister] said at the annual meetings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in Washington.

"By default or design, it really is an economic embargo," he said.

An economic embargo. How terrible!

How were the economic conditions in the three countries a few months ago?

Before the Ebola outbreak intensified, these countries were making remarkable economic progress—particularly Sierra Leone and Liberia, which experienced rapid economic growth in recent years after overcoming decades of civil strife. In 2013, Sierra Leone and Liberia ranked second and sixth among the top 10 countries with the highest GDP growth in the world (albeit their base levels of GDP are very small to begin with). Guinea, while growing more slowly at 2.5 percent in 2013, had high expectations for growth

Just when conditions seemed to be settling down, not only does the Ebola virus hit but also the irrational response from the rest of the world.

In addition to the enormous and tragic loss of human life, the Ebola epidemic is having devastating effects on these West African economies in a variety of essential sectors by halting trade, hurting agriculture and scaring investors.

The long-term destructive effect on the economies coming from the fear:

the largest economic effects of the crisis are not as a result of the direct costs (mortality, morbidity, caregiving, and the associated losses to working days) but rather those resulting from aversion behavior driven by fear of contagion. This in turn leads to a fear of association with others and reduces labor force participation, closes places of employment, disrupts transportation, and motivates some government and private decision-makers to close sea ports and airports.

Keep in mind that the following were estimates of impacts developed nearly a month ago:

these estimates rise to $809 million in the three countries alone. In Liberia, the hardest hit country, the High Ebola scenario sees output hit 11.7 percentage points in 2015 (reducing growth from 6.8 percent to -4.9 percent).

Now, $809 million might not seem to be a high number. Until you think about the estimated GDP of the those countries.

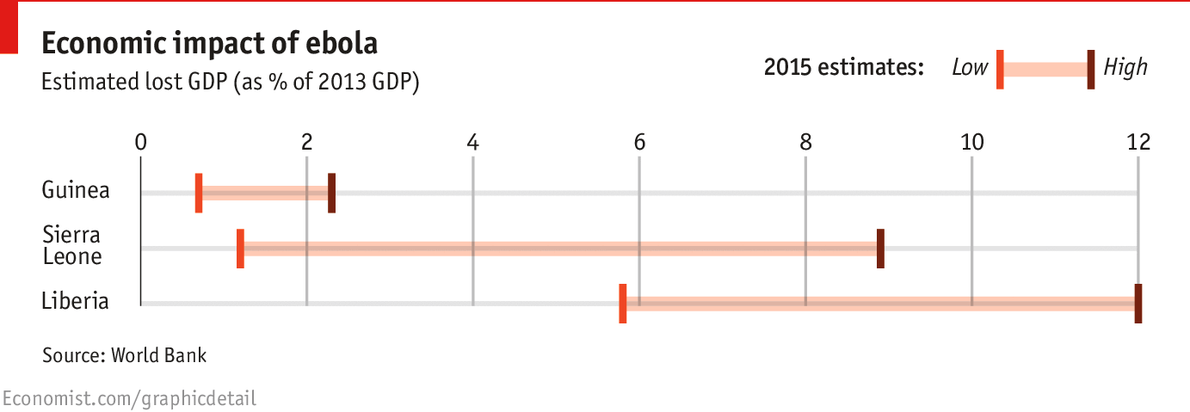

If instead of words, you prefer a picture, here is one from The Economist:

I suppose that it is only a continuation of history when we rich folks in the rich and poor countries decide that all we want to do is to lift up the drawbridges and keep the poor and the hungry and the ill away and on the other side of the moat, and casually remark that they can eat cakes. Some fucked up humans we are!

Have you made your donation to help those fight the good fight? I recommend donating to Doctors Without Borders.

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

Will Liberals laud Walmart?

A year ago--in September 2013--I blogged about Walmart being way ahead of other businesses on at least one aspect that liberals love to talk about. Yet, this news junkie hasn't read anything to that effect from the usual suspects.

So, what should liberals be applauding Walmart for?

Its adoption of green energy--solar power.

In that September 2013 post, I noted:

105 MW. That is huge.

From 65 MW to 105 MW!

You think that the Walmart-bashing, Apple-loving, liberals will cheer this? Will faculty, who even organize their students to boycott Walmart, bring this to their students' attention?

Imagine if left-leaning environmentalist faculty get their students to write to Walmart appreciating the leadership the corporation has shown in this important issue of greener energy sources!

Of course, none of that will happen. For one, we typically see only what we want to see, and we tend to dismiss evidence that does not resonate with our ideological perspectives. Which means that chances are high that the liberal faculty who rail against Walmart and fossil fuels might not even know that Walmart is way ahead of them. For another, even if they are aware of it, chances are pretty good that they won't give the devil its due.

As Slate notes:

So, what should liberals be applauding Walmart for?

Its adoption of green energy--solar power.

In that September 2013 post, I noted:

Among the corporations going solar, the biggest one is Wal-Mart. Yes, that same Wal-Mart that the solar-loving left typically loves to hate. Unlike the left that pushes expensive solar for reasons other than a dollar bottom-line, Wal-Mart does that precisely because it sees money in itNow this update from Slate, which makes the story even more exciting:

105 MW. That is huge.

the company now has more solar capacity than 35 states and the District of Columbia.How was the situation in that post a year ago?

From 65 MW to 105 MW!

You think that the Walmart-bashing, Apple-loving, liberals will cheer this? Will faculty, who even organize their students to boycott Walmart, bring this to their students' attention?

Imagine if left-leaning environmentalist faculty get their students to write to Walmart appreciating the leadership the corporation has shown in this important issue of greener energy sources!

Of course, none of that will happen. For one, we typically see only what we want to see, and we tend to dismiss evidence that does not resonate with our ideological perspectives. Which means that chances are high that the liberal faculty who rail against Walmart and fossil fuels might not even know that Walmart is way ahead of them. For another, even if they are aware of it, chances are pretty good that they won't give the devil its due.

As Slate notes:

Walmart's notoriously ruthless cost-cutting might actually burnish solar power's reputation as an economically viable choice rather than some goofy liberal fixation. The company wouldn't be building out an entire state's worth of capacity if solar didn't make fundamental financial sense. Corporate America doesn't get any more hardheaded—or mainstream—than Walmart, and that's great news for green energy.Indeed. Solar energy might really catch on if people and businesses found out that even the ruthlessly cost-cutting Walmart is going solar in a big way. As they say, follow the money ;)

Tuesday, October 21, 2014

"Pole-pole," not "hakuna matata," in Higher Education

"Pole-pole" was one of the first Swahili phrases that we--the group I was with--were advised to understand during our three-weeks as volunteer-tourists in Tanzania. A phrase that suggests taking things slowly, to ease up, not to get all wound up, not to rush. It was important that we Americans understood this, and approached our daily interactions with Tanzanians that way, given the American drive to get things done. We had to ditch the favored "chop-chop" attitude in favor of "pole-pole."

Even I had problems downshifting to "pole-pole" despite my unhurried approach to many aspects of life. As much as I quote Rumi and wonder why we hurry, I found the "pole-pole" life way too slooooooow.

I suppose I have my own speed in life. I found the Tanzanian life to be slow, while my daughter thinks, even gets annoyed sometimes, that I take the longest time to complete a thought, a sentence! The good thing, at least according to me, is that I don't force others to speed up to my pace, nor do I nag them to slow down to mine.

But, there is one aspect of life where I believe we are messed up with our excessive speed: education.

Instead of taking the time to educate, we are incorrectly focused on a whole bunch of messed-up priorities. (No, this post is not about the wasteful spending on athletics, or on frivolous courses, or ...)

Students and their parents, and taxpayers, have a twisted notion that higher education is about vocational training. Many of these are the same people who oppose vocational education in high schools, and yet want to approach higher education as if it is a trade school! As Taylor notes:

Even I had problems downshifting to "pole-pole" despite my unhurried approach to many aspects of life. As much as I quote Rumi and wonder why we hurry, I found the "pole-pole" life way too slooooooow.

I suppose I have my own speed in life. I found the Tanzanian life to be slow, while my daughter thinks, even gets annoyed sometimes, that I take the longest time to complete a thought, a sentence! The good thing, at least according to me, is that I don't force others to speed up to my pace, nor do I nag them to slow down to mine.

But, there is one aspect of life where I believe we are messed up with our excessive speed: education.

[Educators] are responsible for teaching students how to think critically and creatively about the values that guide their lives and inform society as a whole.Indeed! I agree with Mark Taylor, who is at Columbia, without any reservations whatsoever.

That cannot be done quickly—it will take the time that too many people think they do not have.

Acceleration is unsustainable. Eventually, speed kills.

Instead of taking the time to educate, we are incorrectly focused on a whole bunch of messed-up priorities. (No, this post is not about the wasteful spending on athletics, or on frivolous courses, or ...)

People often ask me how higher education and students have changed in the four decades I have been teaching. While there is no simple answer, the most important changes can be organized under five headings: hyperspecialization, quantification, distraction, acceleration, and vocationalization.Yes, from the faculty side of teaching and learning, hyperspecialization--even at undergraduate education--has been awful!

Since the early 1970s, higher education has suffered from increasing specialization and, correspondingly, excessive professionalization. That has created a culture of expertise in which scholars, who know more and more about less and less, spend their professional lives talking to other scholars with similar interests who have little interest in the world around them. This development has led to the increasing fragmentation of disciplines, departments, and curricula. The problem is not only that far too many teachers and students don’t connect the dots, they don’t even know what dots need to be connected.I like how Taylor puts it: "they don’t even know what dots need to be connected." The "they" includes teachers too.

Students and their parents, and taxpayers, have a twisted notion that higher education is about vocational training. Many of these are the same people who oppose vocational education in high schools, and yet want to approach higher education as if it is a trade school! As Taylor notes:

[It] reflects a serious misunderstanding of what is practical and impractical, as well as the confusion between the practical and the vocational. As the American Academy of Arts and Sciences report on the humanities and social sciences, "The Heart of the Matter," insists, the humanities and liberal arts have never been more important than in today’s globalized world. Education focused on STEM disciplines is not enough—to survive and perhaps even thrive in the 21st century, students need to study religion, philosophy, art, languages, literature, and history. Young people must learn that memory cannot be outsourced to machines, and short-term solutions to long-term problems are never enough.If only I knew how to practice the more famous Swahili phrase, "hakuna matata!"

|

| Source |

Sunday, October 19, 2014

The global war on Muslims is ... stupid and dangerous!

I wonder how a typical Muslim feels.

When in the company of the select few of their innermost circle, when they will have no need to worry about anything and can be completely at ease to express themselves, do Muslims feel their lives are like everybody else's, or do they worry that the global rhetoric and action are seemingly anti-Muslim?

Line up the world's largest economic and military powers of the day.

In the US, there is rabid Islamophobia, especially worrying when it is led by "liberal" atheists like Bill Maher and Sam Harris.

France has issues even with the veil.

Russia's shirtless Putin doesn't ever come across like he might want to accommodate Muslims.

Israel.

India.

And, of course, the "war on terror" subliminally and explicitly leading people to equate Muslims with terrorists! It could easily seem like there is a global war on Muslims!

China has its own way to treat Muslims. Particularly those in Xinjiang--the Uighurs. You push a group hard enough and at some point they are bound to react with "I'm mad as hell" and will demonstrate how they can't take it anymore. I am saddened, but not surprised at all, with this latest incident:

This latest incident suggests that the intensity of violence has increased: last May, about 43 killed, and in July nearly a 100 died, in a "pattern of recent attacks in which Uighur assailants, often using crude weapons, target Han civilians as well as Uighur police officers and government officials."

The fucked up Beijing government is so panicky about the Uighurs that:

It is not the Beijing government that is fucked up. We are!

When in the company of the select few of their innermost circle, when they will have no need to worry about anything and can be completely at ease to express themselves, do Muslims feel their lives are like everybody else's, or do they worry that the global rhetoric and action are seemingly anti-Muslim?

Line up the world's largest economic and military powers of the day.

In the US, there is rabid Islamophobia, especially worrying when it is led by "liberal" atheists like Bill Maher and Sam Harris.

France has issues even with the veil.

Russia's shirtless Putin doesn't ever come across like he might want to accommodate Muslims.

Israel.

India.

And, of course, the "war on terror" subliminally and explicitly leading people to equate Muslims with terrorists! It could easily seem like there is a global war on Muslims!

China has its own way to treat Muslims. Particularly those in Xinjiang--the Uighurs. You push a group hard enough and at some point they are bound to react with "I'm mad as hell" and will demonstrate how they can't take it anymore. I am saddened, but not surprised at all, with this latest incident:

An attack on a farmers market in the western Chinese region of Xinjiang has reportedly left at least 22 people dead and dozens injured, Radio Free Asia, the news service financed by the American government, has reported.Awful!

Radio Free Asia said on Saturday that the rampage, which took place Oct. 12 in Kashgar Prefecture, was carried out by four men armed with knives and explosives who attacked police officers and merchants before the men were shot dead by the police. Most of the victims were ethnic Han Chinese and the assailants were ethnic Uighur, the news service said, citing local police officials.

Violence has been mounting in recent months despite a crackdown on what the authorities describe as Islamic-inspired terrorism. Human rights advocates say harsh security measures and tightened restrictions on religious practices are aggravating discontent among Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking minority who complain about job discrimination and Han migration to the region, which many see as an effort to dilute their ethnic identity.The Beijing government is all fucked up! How supremely confident in their inhuman approach they are when they try their best to wipe out the religious and ethnic identities that humans value. Heck, if even the peaceful Tibetan lamas will set fire to themselves because they can't take it anymore, should we be surprised when the less peaceful humans decide to take up arms, however crude they might be?

This latest incident suggests that the intensity of violence has increased: last May, about 43 killed, and in July nearly a 100 died, in a "pattern of recent attacks in which Uighur assailants, often using crude weapons, target Han civilians as well as Uighur police officers and government officials."

The fucked up Beijing government is so panicky about the Uighurs that:

Ilham Tohti, a scholar who has been an outspoken critic of the government’s treatment of people of his Uighur ethnicity, was sentenced to life in prison for separatism. The ruling by a court in Urumqi, the capital of his native region of Xinjiang, was the harshest known sentence in years for someone convicted of a non-violent political crime in China. By jailing Mr Tohti, who says he supports Chinese rule, the government has signalled a desire to silence even moderate voices of dissent in Xinjiang, where Uighur separatists have often resorted to violence to express their grievances.Why target him?

No other Uighur inside the country has come close to speaking out on such issues with his persistence. But the government, though unsettled by his pro-Uighur sentiments, has for a long time also worried about how to handle him: he taught economics at a prestigious university in Beijing that was established precisely to win over ethnic minorities like China’s Uighurs. Arresting such a calmly spoken academic risked fuelling even more sympathy abroad for the plight of Uighurs, most of whom are Muslims and many of whom chafe at China’s rule in Xinjiang.I guess the world tolerates China's behavior because we are all happy with everything from cheap plastic stuff to iPhones manufactured there. Who cares about some Muslim group in China that is ill-treated by the government when we deserve all the goodies, right?

It is not the Beijing government that is fucked up. We are!

Saturday, October 18, 2014

To love whom they please and to marry whom they love

As a kid, as a teenager, and later even as an adult in India, I hadn't known a single gay person. For that matter, I hadn't known a single black, or a Mexican, or an Arab, or a white ... But, I had at least seen black and Mexican and white characters in movies, and read about them in fiction. I had no idea about gays. Well, the only thing I knew about gays was when in college there was a "wink-wink" about a guy.

Sex and sexuality was not talked about in the old country. An old Tamil saying captures well the essence: "மன்மதக்கலை சொல்லி தெரிவதில்லை" (the art of the (god of) love is not taught and learnt.) What I knew, messed up and incorrect that was--as I would find out much later in life--I knew from friends and fellow-classmates, who were also equally ill-informed.

And then I came to America.

I distinctly recall being shocked, intrigued, a month or so into my life in the new country, when I saw two young women locking lips in the public, outside the apartment building, just like how a young man and woman typically displayed their affections in public.

Since that first exposure, it has been one heck of a rapid education about love, homosexuality, and the politics of it all.

It is not only I who have moved, and moved rapidly, from not knowing anything to getting to know gays and becoming very good friends with them:

While I can claim ignorance of youth for the errors that I made in plenty, I have always felt awful about the "wink wink" comments about that college guy. I have no idea whether he was/is gay; but, in any case, I suppose I can come clean with a public apology via this post.

Sex and sexuality was not talked about in the old country. An old Tamil saying captures well the essence: "மன்மதக்கலை சொல்லி தெரிவதில்லை" (the art of the (god of) love is not taught and learnt.) What I knew, messed up and incorrect that was--as I would find out much later in life--I knew from friends and fellow-classmates, who were also equally ill-informed.

And then I came to America.

I distinctly recall being shocked, intrigued, a month or so into my life in the new country, when I saw two young women locking lips in the public, outside the apartment building, just like how a young man and woman typically displayed their affections in public.

Since that first exposure, it has been one heck of a rapid education about love, homosexuality, and the politics of it all.

It is not only I who have moved, and moved rapidly, from not knowing anything to getting to know gays and becoming very good friends with them:

In the 1950s gay sex was illegal nearly everywhere. In Britain, on the orders of a home secretary who vowed to “eradicate” it, undercover police were sent out to loiter in bars, entrap gay men and put them in jail. In China in the 1980s homosexuals were rounded up and sent to labour camps without trial. All around the world gay people lived furtively and in fear. Laws banning “sodomy” remained in some American states until 2003.A remarkable transformation in our collective attitudes.

Today gay sex is legal in at least 113 countries.

What could help spread tolerance? If the past half-century is any guide, the prime movers will be gay people themselves. The more visible they are, the more normal they will seem. These days 75% of Americans say they have gay friends or colleagues, up from only 24% in 1985. But it is hard to be the first to come out in a country where that means prison or worse.How are things in the old country?

...

For those who cling to the notion of progress, it is hard to believe that tolerance will not spread. After all, gay people are not demanding special treatment, just the same freedoms that everyone else takes for granted: to love whom they please and to marry whom they love.

In India the past decade has brought considerable change. The first national magazine for gay people, Pink Pages, was launched in 2009. Gay-pride marches, if not necessarily very large ones, are a common sight in big cities. Bollywood has produced sympathetic films.With a party that actively talks up Hindu nationalism, odds are far from favorable for India's parliament to pass laws legalizing homosexuality. But then politics works in strange ways.

Yet even if it is becoming slightly easier among India’s elite to be openly gay, almost no one in public life dares declare it. And the legal position for homosexuals is in flux. In July 2009 a high court ruled that the ban on “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” in the penal code violated India’s constitution, a ruling which in effect decriminalised gay sex. In December 2013 two Supreme Court judges overturned the ruling. They said that parliament could pass a law to legalise gay sex; at the moment, that looks unlikely.

While I can claim ignorance of youth for the errors that I made in plenty, I have always felt awful about the "wink wink" comments about that college guy. I have no idea whether he was/is gay; but, in any case, I suppose I can come clean with a public apology via this post.

Friday, October 17, 2014

I like to live in America!

A few years ago, when I was asked for advice, I told the young person that to me living in America is not really about the material affluence, which I do enjoy, yes. And, if affluence were all that was of interest, then there are plenty of other places on the planet now where one can earn planeloads of money--perhaps even more than what can be earned in America. One can even stay put in the country of birth and earn in plenty.

Therefore, my advice was that coming to America should be about wanting a certain way of living and not really about the money. "Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" that embraces liberal democracy and values the individual's rights.

The fact that these values are precious to me, and are why I love living here in America, does not mean that I believe these are universal values either. In my atheist framework, we are born, we live, we die and, therefore, it is up to each one of us to figure out how to live. If others choose a completely different framework, and live happily or unhappily as a result of that, well, it matters not to me as long as they don't compel me to live according to their rules. Nor do I find it necessary for me to try to convert others into my way of thinking--it simply ain't my business.

Thus, I often note that it is up to people to draw up their own social contracts with their fellow citizens. All I know is that I do not care to live in countries where their social contracts are practically incompatible with my approach to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." Even after all these years, I shudder recalling the experience of the computer returning a "site banned" message on the screen when all I did was try to access my work emails during a visit to a country whose name begins with a U and ends with an S, and when staying in a city with a name that begins with a D and ends with an I. (You solved the puzzle? hehehe!)

It also pisses me off when Americans think it is their responsibility to spread the idea of individual rights and the pursuit of happiness to the rest of the world, overtly and covertly. This missionary zeal to export the American, and Western, model is also what the talented wordsmith and ideas man, Pankaj Mishra tackles in a lengthy essay, in which he notes:

But, neither do I want my government to tell people in other countries how they ought to live and govern themselves. As Mishra notes:

Whether it is via the economics of the market or the politics of democracy, a reckless export causes, and has caused, a lot of suffering.

Therefore, my advice was that coming to America should be about wanting a certain way of living and not really about the money. "Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" that embraces liberal democracy and values the individual's rights.

The fact that these values are precious to me, and are why I love living here in America, does not mean that I believe these are universal values either. In my atheist framework, we are born, we live, we die and, therefore, it is up to each one of us to figure out how to live. If others choose a completely different framework, and live happily or unhappily as a result of that, well, it matters not to me as long as they don't compel me to live according to their rules. Nor do I find it necessary for me to try to convert others into my way of thinking--it simply ain't my business.

Thus, I often note that it is up to people to draw up their own social contracts with their fellow citizens. All I know is that I do not care to live in countries where their social contracts are practically incompatible with my approach to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." Even after all these years, I shudder recalling the experience of the computer returning a "site banned" message on the screen when all I did was try to access my work emails during a visit to a country whose name begins with a U and ends with an S, and when staying in a city with a name that begins with a D and ends with an I. (You solved the puzzle? hehehe!)

It also pisses me off when Americans think it is their responsibility to spread the idea of individual rights and the pursuit of happiness to the rest of the world, overtly and covertly. This missionary zeal to export the American, and Western, model is also what the talented wordsmith and ideas man, Pankaj Mishra tackles in a lengthy essay, in which he notes:

In the 21st century that old spell of universal progress through western ideologies – socialism and capitalism – has been decisively broken. If we are appalled and dumbfounded by a world in flames it is because we have been living – in the east and south as well as west and north – with vanities and illusions: that Asian and African societies would become, like Europe, more secular and instrumentally rational as economic growth accelerated; that with socialism dead and buried, free markets would guarantee rapid economic growth and worldwide prosperity. What these fantasies of inverted Hegelianism always disguised was a sobering fact: that the dynamics and specific features of western “progress” were not and could not be replicated or correctly sequenced in the non-west. ...I would not want to live in China or Turkey, but would love to spend a few days as a traveler in those countries. Living there for an extended period of time will call for thinking about the issues that surround me. For instance, at the high school reunion a couple of years ago, a classmate asked another classmate--who is now an American expat working and living in China--a few questions about his life there. And asked for some examples. The Indian-American expat in China talked about how in a matter of months the Chinese government got rid of an antiquated road system that did not have the capacity for modern needs and built a multi-lane freeway. "What happened to the homes there?" the classmate asked. The expat said he assumed that the government paid the people a fair compensation. "If they protested?" was the follow-up. The expat shrugged his shoulder. "Not my problem" he said. It was another reminder that I cannot live in a society and simply shrug my shoulder and say "not my problem." A mercenary existence that does not appeal to me.

China has more recently achieved a form of capitalist modernity without embracing liberal democracy. Turkey now enjoys economic growth as well as regular elections; but these have not made the country break with long decades of authoritarian rule. The arrival of Anatolian masses in politics has actually enabled a demagogue like Erdoğan to imagine himself as a second Atatürk.

But, neither do I want my government to tell people in other countries how they ought to live and govern themselves. As Mishra notes:

Recklessly exported worldwide even today, the west’s successful formulas have continued to cause much invisible suffering.Exactly!

Whether it is via the economics of the market or the politics of democracy, a reckless export causes, and has caused, a lot of suffering.

The result is endless insurgencies and counter-insurgencies, wars and massacres, the rise of such bizarre anachronisms and novelties as Maoist guerrillas in India and self-immolating monks in Tibet, the increased attraction of unemployed and unemployable youth to extremist organisations, and the endless misery that provokes thousands of desperate Asians and Africans to make the risky journey to what they see as the centre of successful modernity.Yep. Why meddle around? I am not happy that Indians have elected to power a maniac whose rise to power was fueled by Hindu nationalism, nor am I happy with the Party in China, or with Russia's Putin, or ... the list is endless. I blog about them. I critique them, yes, as much as I critique America too--after all, America is no Eden. But, at the end of it all, I recognize that those are their problems not mine or America's.

It should be no surprise that religion in the non-western world has failed to disappear under the juggernaut of industrial capitalism, or that liberal democracy finds its most dedicated saboteurs among the new middle classes. The political and economic institutions and ideologies of western Europe and the United States had been forged by specific events – revolts against clerical authority, industrial innovations, capitalist consolidation through colonial conquest – that did not occur elsewhere. So formal religion – not only Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, and the Russian Orthodox Church, but also such quietist religions as Buddhism – is actually now increasingly allied with rather than detached from state power. The middle classes, whether in India, Thailand, Turkey or Egypt, betray a greater liking for authoritarian leaders and even uniformed despots than for the rule of law and social justice.

Wednesday, October 15, 2014

It will be a sad day when "Sanitas Per Escam" becomes"Health via Soylent"

The vegetable vendor is one of the many un-American experiences when visiting with the parents in the old country. Pushing his cart, he bellows the names of the vegetables he has to sell. He is so loud that sometimes I can hear him over the phone if I happen to call my parents at the time he is hawking his goods.

He brings the vegetables to people. Round the corner from where my parents live is a modern supermarket that sells vegetables and more. The old and the new coexist in the old country. But, as with many other aspects of life, the vendor pushing his cart is also becoming a rarity.

Here in my adopted country, cities like where I live feature Saturday Markets, through the growing season and when the weather is not atrocious--here, it is from early spring until mid-fall. Instead of vendors pushing their carts along the neighborhood streets, they congregate at a place.

The Saturday Market is a diversion from the routine, which is to get the supplies from supermarkets. "[Buying] food can even be enjoyed as a leisure pursuit, rather than a daily chore"

In generations gone by, before the ubiquity of refrigeration and food preservatives, people were forced to go shopping every day – visiting half-a-dozen different shops to get what they needed for a single family meal. ... The arrival of supermarkets in the Fifties and Sixties was revolutionary. For the first time in history, ordinary people had access to an array of exotic foods from around the world, never before available under one roof. And, what’s more, it was affordable; large chains were able to buy mass-produced food in such bulk that food producers were lining up to offer them the lowest prices possible.

Even in the old country, mother does not buy vegetables every single day from that vendor, or from the supermarket, thanks to the fridge at home. It is a different world there, here, and everywhere.

But, I suppose even buying groceries in order to cook at home is becoming rarer anymore. Fancy kitchens seem to be more for decorative purposes than for cooking at home, it feels like. It is also a phenomenal piece of evidence on the choices we have, without being restricted to eat at home after spending hours working with primary ingredients. As Rachel Laudan noted:

If we romanticize the past, we may miss the fact that it is the modern, global, industrial economy (not the local resources of the wintry country around New York, Boston, or Chicago) that allows us to savor traditional, fresh, and natural foods. Fresh and natural loom so large because we can take for granted the processed staples—salt, flour, sugar, chocolate, oils, coffee, tea—produced by food corporations.

Even though cooking at home is easier with pre-processed ingredients, so that people like me can jump into a step 6 of the process, apparently quite a few think that cooking at home is a time consuming chore. Why?

According to the researchers, the answer has to do with a reduction of mental effort. ‘Perhaps the most important and clear-cut effect of packaged foods is that they reduce the complexity of meal planning,’ they write. ‘The family chef can invest less time thinking about the week’s meals.’

In other words, in a world where nearly 100,000 new food and drink products are added to supermarket shelves each year, convenience food offers a valuable freedom from decision-making – a signposted shortcut through the bewildering cornucopia and competing claims of the contemporary food environment.

And, therefore, there are even folks even now who would rather chug synthesized "nutrition." Even though I intellectually and emotionally understand the changes that have happened even within my lifetime thus far, reading about "Soylent," a few months ago, in "the end of food" made me highly uncomfortable, to say the least.

Soylent has been heralded by the press as “the end of food,” which is a somewhat bleak prospect. It conjures up visions of a world devoid of pizza parlors and taco stands—our kitchens stocked with beige powder instead of banana bread, our spaghetti nights and ice-cream socials replaced by evenings sipping sludge. But, Rhinehart says, that’s not exactly his vision. “Most of people’s meals are forgotten,” he told me. He imagines that, in the future, “we’ll see a separation between our meals for utility and function, and our meals for experience and socialization.”

When the author of that piece lived a three-day weekend essentially on Soylent, she realized how much eating is more than merely about food:

You begin to realize how much of your day revolves around food. Meals provide punctuation to our lives: we’re constantly recovering from them, anticipating them, riding the emotional ups and downs of a good or a bad sandwich. With a bottle of Soylent on your desk, time stretches before you, featureless and a little sad. On Saturday, I woke up and sipped a glass of Soylent. What to do? Breakfast wasn’t an issue. Neither was lunch. I had work to do, but I didn’t want to do it, so I went out for coffee. On the way there, I passed my neighborhood bagel place, where I saw someone ordering my usual breakfast: a bagel with butter. I watched with envy. I wasn’t hungry, and I knew that I was better off than the bagel eater: the Soylent was cheaper, and it had provided me with fewer empty calories and much better nutrition. Buttered bagels aren’t even that great; I shouldn’t be eating them. But Soylent makes you realize how many daily indulgences we allow ourselves in the name of sustenance.

Eating is not merely about food. It is about relationships of various kinds:

With the people from whom we buy the groceries.

With the people who share meals with us.

With people who listen to our stories about dining experiences.

Oh well, maybe this is more evidence that I am becoming an old curmudgeon!

Tuesday, October 14, 2014

No reason to complain

He brought the hand-held mirror towards me. Even before he could raise it, I told him "it's ok. I'm sure it is fine."

"Are you sure?" he asked with a smile.

"Am positive. Haven't had any reason to complain thus far" I replied.

He put the mirror down on the counter. I felt him tapping my shoulder, in a warm and friendly manner. "I wish my wife always said she had no reason to complain" he said with a big laugh.

I joined in the laughter.

That is how my latest haircut session ended. After that, I got out of the seat, paid up, and left.

I love such unscripted human interactions for the flavor they add to the everyday life.

Like the other day when I was on the bike path. I overtook a couple--perhaps only a few years older than me--when I heard the man tell the woman, intentionally loudly to make sure I heard him, "if I walked at his pace, I surely will lose a lot of weight."

I turned around and gave them a big smile--a smile that was bigger than what I sport now while typing this. They chuckled in return.

Or like a few days ago when I was at the checkout counter at my regular grocery store. Wendy smiled big time and said that she didn't have any jokes for me. "Hey Kathy, do you have any jokes for Sriram?" she asked.

Kathy, who was at the adjacent counter walked over to me. She tilted her head. She thought. "I have a Halloween joke for you."

"Tell me" I said.

"You know from all the jokes that the chicken crossed the road" she paused for the effect. "But the skeleton did not cross the road. Why did the skeleton not cross the road?"

As is the custom in such groaner contexts, I asked her, "ok, why did the skeleton not cross the road?"

"Because he had no guts."

We all laughed.

Is it because I am older that I am able to participate in such interactions? In all these contexts, the other parties were all my age or older. Were we all able to enjoy those moments only because we are not young? If we had had these intersections in life when we were in our twenties, it would have been different?

Perhaps to experience life from its silly to the profoundly happy and grieving moments requires one to have lived a few years, witnessed the ups and the downs, and been far and away from where we were born and raised.

It's a wonderful life, indeed!

"Are you sure?" he asked with a smile.

"Am positive. Haven't had any reason to complain thus far" I replied.

He put the mirror down on the counter. I felt him tapping my shoulder, in a warm and friendly manner. "I wish my wife always said she had no reason to complain" he said with a big laugh.

I joined in the laughter.

That is how my latest haircut session ended. After that, I got out of the seat, paid up, and left.

I love such unscripted human interactions for the flavor they add to the everyday life.

Like the other day when I was on the bike path. I overtook a couple--perhaps only a few years older than me--when I heard the man tell the woman, intentionally loudly to make sure I heard him, "if I walked at his pace, I surely will lose a lot of weight."

I turned around and gave them a big smile--a smile that was bigger than what I sport now while typing this. They chuckled in return.

Or like a few days ago when I was at the checkout counter at my regular grocery store. Wendy smiled big time and said that she didn't have any jokes for me. "Hey Kathy, do you have any jokes for Sriram?" she asked.

Kathy, who was at the adjacent counter walked over to me. She tilted her head. She thought. "I have a Halloween joke for you."

"Tell me" I said.

"You know from all the jokes that the chicken crossed the road" she paused for the effect. "But the skeleton did not cross the road. Why did the skeleton not cross the road?"

As is the custom in such groaner contexts, I asked her, "ok, why did the skeleton not cross the road?"

"Because he had no guts."

We all laughed.

Is it because I am older that I am able to participate in such interactions? In all these contexts, the other parties were all my age or older. Were we all able to enjoy those moments only because we are not young? If we had had these intersections in life when we were in our twenties, it would have been different?

Perhaps to experience life from its silly to the profoundly happy and grieving moments requires one to have lived a few years, witnessed the ups and the downs, and been far and away from where we were born and raised.

It's a wonderful life, indeed!

Monday, October 13, 2014

Why the Ebola panic in the US? We are certified idiots, that's why!

Consider the following:

This ought to make us scared to venture out of our homes, right? Yet, we carry on with our lives. We drive, we go to the stores, and merrily go about as if we don't care a damn about the probability that we will die in a road accident. Or, die from a senseless random bullet.

Ironically, we are also the same people shit scared about Ebola. About Ebola, here in the United States!!!

James Surowiecki writes in the New Yorker that there is an even worse danger, an evil one, that awaits us this very minute: the flu virus.

It is a shame though we are so afraid of Ebola only because it entered our territory. As long as it was merely something that killed some people somewhere in Africa, we couldn't care less. What a shame, what a tragedy!

Until then, do us all a favor and stop looking at your smartphone when driving. Get yourself a flu shot. Walk an hour every day and eat healthily. Stop watching cable news.

More than anything else, keep calm and carry on.

In 2010, transport accidents in the U.S. accounted for 38,000 deaths, with more than two-thirds of these fatalities occurring among men.Not merely in 2010, but every year we could expect more than 30,000 to die from transport accidents. Every year, we can expect more than 15,000 from homicides.

This ought to make us scared to venture out of our homes, right? Yet, we carry on with our lives. We drive, we go to the stores, and merrily go about as if we don't care a damn about the probability that we will die in a road accident. Or, die from a senseless random bullet.

Ironically, we are also the same people shit scared about Ebola. About Ebola, here in the United States!!!

James Surowiecki writes in the New Yorker that there is an even worse danger, an evil one, that awaits us this very minute: the flu virus.

No one is asking “What Scares You More: Ebola or the Flu?”And they should be asking that because:

We know, based on past experience, that the upcoming flu season will kill thousands of Americans and send hundreds of thousands to the hospital. Yet the press seems relatively diffident about raising an alarm about this threat; its flu coverage has none of the high-pitched anxiety that suffuses writing about EbolaWhatever happened to evidence-based reasoning and thinking skills that we should have picked up even from a basic high school education?

As a myriad of studies have shown, we tend to underestimate the risk of common perils and overestimate the risk of novel events. We fret about dying in a terrorist attack or a plane crash, but don’t spend much time worrying about dying in a car accident. We pay more attention to the danger of Ebola than to the far more relevant danger of flu, or of obesity or heart disease. It’s as if, in certain circumstances, the more frequently something kills, the less anxiety-producing we find it.We are certified idiots with no "civic scientific literacy." That is what I can conclude. There is simply no other explanation.

The real problem is that irrational fears often shape public behavior and public policy. They lead us to over-invest in theatre (such as airport screenings for Ebola) and to neglect simple solutions (such as getting a flu shot).Irrational fear leading to panic. Sheer panic. As Michael Specter notes:

Our response to pandemics—whether SARS, avian influenza, MERS, or Ebola—has become predictable. First, there is the panic. Then, as the pandemic ebbs, we forget. We can’t afford to do either.We are certified idiots.

It is a shame though we are so afraid of Ebola only because it entered our territory. As long as it was merely something that killed some people somewhere in Africa, we couldn't care less. What a shame, what a tragedy!

Rob Carlson, the author of “Biology Is Technology,” who has written widely about genetic engineering and vaccine development, says, “We could have pushed the development of a synthetic Ebola vaccine a decade ago. We had the skills, but we chose not to pursue it. Why? Because we weren’t the people getting sick.”Yep, we could have made tremendous advances:

Of course, we could all rest easier if there were an anti-Ebloa vaccine. That is something that could protect people far more effectively than any tightening of security at airports or along the border. Dr. Francis Collins, head of the National Institutes of Health said the NIH has been working toward that goal since 2001 and would have gotten there, if not for one thing.Well, now that we are so worried that we could get sick, let us hope that at least this panic will lead us to develop an Ebola vaccine that will eliminate the virus similar to how we got rid of small pox.

“Frankly, if we had not gone through our 10-year slide in research support, we probably would have had a vaccine in time for this [outbreak] that would’ve gone through clinical trials and would have been ready,” Collins told the Huffington Post.

Why, you may ask, did the NIH not have the money to do the work that, Collins, said, “would have made all the difference?” Easy answer: Republican budget-cutting fanatics in Congress have held down funding for the NIH and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for a more than a decade.

Until then, do us all a favor and stop looking at your smartphone when driving. Get yourself a flu shot. Walk an hour every day and eat healthily. Stop watching cable news.

More than anything else, keep calm and carry on.

Sunday, October 12, 2014

What does SAT expand to? Student Affluence Test!

One of the best lines ever from the political theatre that I have had the pleasure of watching after moving to the country was the one delivered by Ann Richards, when I was just about getting acquainted with the actors and their affiliations, by which I mean politicians and their parties:

Bush, of course, went on to win the elections. A few years after that, Ann Richards lost the governorship to Bush's son, "W." And then she lived long enough to see "W" also get elected as president, and then get re-elected as well.

Being born even with a silver foot in the mouth helps. It helps a lot. To make it is relatively easy when born into the "correct" contexts.

We discount the head start that the silver spoon kids get because of the other narrative that we want to believe--the Horatio Alger myth of rags to riches, from nowhere to the White House. We are so desperate to believe in the myth that will go to any length to be in denial of the reality, which I have blogged often here, sometimes as choose your parents well.

Today's evidence is from SAT scores. It will be a rare older American adult who does not remember his/her SAT scores from the high school days. The number leaves a permanent imprint in one's mind. Because of the repercussions that the score has for college, scholarship, and the rest of one's life.

It is increasingly clear that the SAT score is highly correlated with the silver spoon effect:

The problem is glaringly obvious--you can't choose your parents.

So, what happens then if your parents happen to be, say, high school educated blacks who live a blue-collar life in the low-income neighborhood that has awful schools? Tough luck, kid! It is your fault that you didn't choose your parents well!

Now, think about the WSJ's report from just a few months ago:

Poor George, ... he can't help it ... he was born with a silver foot in his mouth.It was the best of the show business in America and I was hooked. I remain a political junkie to this day, sadly! ;)

Bush, of course, went on to win the elections. A few years after that, Ann Richards lost the governorship to Bush's son, "W." And then she lived long enough to see "W" also get elected as president, and then get re-elected as well.

Being born even with a silver foot in the mouth helps. It helps a lot. To make it is relatively easy when born into the "correct" contexts.

We discount the head start that the silver spoon kids get because of the other narrative that we want to believe--the Horatio Alger myth of rags to riches, from nowhere to the White House. We are so desperate to believe in the myth that will go to any length to be in denial of the reality, which I have blogged often here, sometimes as choose your parents well.

Today's evidence is from SAT scores. It will be a rare older American adult who does not remember his/her SAT scores from the high school days. The number leaves a permanent imprint in one's mind. Because of the repercussions that the score has for college, scholarship, and the rest of one's life.

It is increasingly clear that the SAT score is highly correlated with the silver spoon effect:

On average, students in 2014 in every income bracket outscored students in a lower bracket on every section of the test, according to calculations from the National Center for Fair & Open Testing (also known as FairTest), using data provided by the College Board, which administers the test.Now, before you condemn that finding as something from a loony left publication, well, it is from the capitalist-friendly Wall Street Journal. As I noted in a different context, if even the WSJ or the Economist is reporting about something that I have often worried about, it then means that the shit has hit the fan. Game over, folks. The end. Finito. The fat lady has sung.

Students from the wealthiest families outscored those from the poorest by just shy of 400 points. Given the widespread use of the SAT in college admissions, the implications are obvious: Not only are the wealthiest families best equipped to pay for college, their kids on average are more likely to post the sort of scores that make admissions easy.

Family wealth allows parents to locate in neighborhoods with better schools (or spring for private schools). Parents who are themselves college educated tend to make more money, and since today’s high school seniors were born in the mid-1990s, many of the wealthiest and best-educated parents themselves came of age when the tests were of crucial importance. When the SAT is crucial to college, college is crucial to income, and income is crucial to SAT scores, a mutually reinforcing cycle develops.Yep, when you choose your parents well, a mutually reinforcing cycle begins.

The problem is glaringly obvious--you can't choose your parents.

So, what happens then if your parents happen to be, say, high school educated blacks who live a blue-collar life in the low-income neighborhood that has awful schools? Tough luck, kid! It is your fault that you didn't choose your parents well!

Now, think about the WSJ's report from just a few months ago:

Proving the adage that all of life is like high school, plenty of employers still care about a job candidate's SAT score. Consulting firms such as Bain & Co. and McKinsey & Co. and banks like Goldman Sachs Group Inc. ask new college recruits for their scores, while other companies request them even for senior sales and management hires, eliciting scores from job candidates in their 40s and 50s.Yep, choosing the parents well is an awesome strategy--don't worry about the silver foot in your mouth because it will all work out in your favor, and you can even proudly beat up on others who can't make it despite all the "equal opportunity" that the land of the free provides!

Americans lack "civic scientific literacy." Take that from us Indian-Americans!

It is not an every day happening when the New York Review of Books features a piece by an author with an Indian name.

And that too a South Indian name.

And, a Tamil name at that.

So, even before I got to reading that piece, I clicked on the author byline, which was darn impressive:

There it was on Wikipedia:

Her photo at the Wiki page made me do a double-take, because she looks so much like the comedian/actress Mindy Kaling:

More material to support my "the Indians are coming! the Indians are coming!!!" joke ;)

Anyway, back to the original point of departure: the NYRB piece itself. What is it about? On science, scientific method, and why the public, especially Americans, don't seem to understand what science is and what scientists do. Natarajan writes that the public seems to have a problem with the "provisionality" that accompanies scientific findings.

Isn't that what I have been harping on all the time? I repeatedly tell students, blog here, that teaching is not about factoids, and that tests and exams should not be focused on the ability of students to recall information from memory within that defined time. Instead, education ought to be about concepts and how to think with them. Feels great to find validation for my approach in an essay by a fellow Tamil-Indian-American!

And that too a South Indian name.

And, a Tamil name at that.

So, even before I got to reading that piece, I clicked on the author byline, which was darn impressive:

Priyamvada Natarajan is a Professor in the Departments of Astronomy and Physics at Yale. She is the author of a forthcoming book on the acceptance of radical scientific ideas. (October 2014)Naturally, to this curious guy, the next step was to do a Google search, which pulled up her Wikipedia page. She has to be somebody, right, to have Wiki page? I mean, do you have a Wiki page? ;)

There it was on Wikipedia:

Priya Natarajan was born in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu in India to academic parents. She is one of three children. Natarajan grew up in Delhi, India and studied at Delhi Public School, R. K. Puram.From Coimbatore to Yale! A female scientist. Awesome! You read her bio at the Yale page and, if you are like me, you will wonder how people like her and Atul Gawande do all those things they do when I think it is a big achievement when I boil eggs!

Her photo at the Wiki page made me do a double-take, because she looks so much like the comedian/actress Mindy Kaling:

|

| This is not Mindy Kaling ;) |

Anyway, back to the original point of departure: the NYRB piece itself. What is it about? On science, scientific method, and why the public, especially Americans, don't seem to understand what science is and what scientists do. Natarajan writes that the public seems to have a problem with the "provisionality" that accompanies scientific findings.

the general public has trouble understanding the provisionality of science. Provisionality refers to the state of knowledge at a given time.Natarajan defines provisionality as:

a slow and gradual honing and growing sophistication of our understanding, driven by accumulating data enabled by the invention of ever-newer instruments.I suppose it can be difficult to grasp the idea that what is held as "scientific" today could be thrown out a few years from now if it is found to be incorrect or an incomplete explanation. So, what can be done? Anything in the education process itself?

The biologist Jon D. Miller of the University of Michigan has been advocating a new standard of “civic scientific literacy,” by which he means a basic level of scientific understanding that would be necessary to make sense of public policy issues involving science or technology. He proposes the teaching of scientific concepts rather than the retention of information. Since the old model is ill-suited to the current pace of scientific and technological progress, the public needs to learn how to reason in the evidence-based manner that is central to science.Did you catch that? "the teaching of scientific concepts rather than the retention of information."

Isn't that what I have been harping on all the time? I repeatedly tell students, blog here, that teaching is not about factoids, and that tests and exams should not be focused on the ability of students to recall information from memory within that defined time. Instead, education ought to be about concepts and how to think with them. Feels great to find validation for my approach in an essay by a fellow Tamil-Indian-American!

Friday, October 10, 2014

Is it possible to pull academia's head out of the clouds?