That's what

Louis Menand asks, when he writes:

If someone described to you an ancient civilization in which, every four

years, at great expense, citizens convened to watch a carefully selected

group perform a series of meticulously preset routines, and in which

the watching was thought of not as a duty but as a hugely anticipated

and unambiguously pleasurable experience, you would guess that,

socially, this ritual was doing a lot of work. You would assume that it

was instilling, or reinforcing, or rebooting attitudes and beliefs that

this hypothetical civilization regarded—maybe correctly, maybe just

superstitiously—as vital to its functioning. You would say that the

spectacle had a content. Do these Summer Games have a content? What are

we really watching when we watch the Olympics?

It is one heck of an interesting question. What are we watching, and why are watching?

The modern Olympics are a model example of what the historians Eric Hobsbawm

and Terence Ranger have called invented traditions—ritualized official

or quasi-official events, often presented as revivals of ancient

practices or in other ways designed to imply continuity with the distant

past.

Well, why would we want to invent such traditions anyway? Why these rituals every four years?

Modern societies are still obsessed with these secular rituals, in

part because almost all of them have become successfully commercialized.

Maybe they offer an illusion of permanence and continuity in a world

characterized mainly by mobility, change, and uncertainty. No matter

what happens to us next year, there will be a Super Bowl. Or maybe they

feed our tribal instincts, stimulate the irrational basis of loyalty to

our community or our country. Even the most cosmopolitan American viewer

of the Olympics has a hard time not rooting for the American. If you

watch, you don’t just want to see how it comes out. You care who wins.

And,

despite the virtuous talk about the honor of competing and the comity

of sport—and the talk is virtuous, and fine as far as it goes—winning

really is what the spectacle is all about.

Hmmm .... Menand seems to be voicing that ultimate bottom-line often quoted here in the US:

Winning isn't everything; it's the only thing.

To me, what was way more interesting than anything else in the essay was the lack-of-sports-enthusiasm that Menand describes in his family when he was growing up because of "an aversion to the belief" that

the ability to run faster or throw farther than other people is a

contribution to the common good, and that we ought to honor the athlete

in the same way that we honor the artist and the statesman.

Now, if only Menand would pursue that thought in another essay of his.

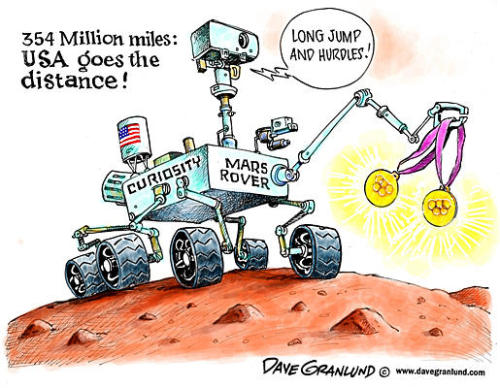

Here is one real-world situation that reflects that thought: NASA successfully landed Curiosity on a planet about 150 million miles away. And it took more than eight months to travel from here.

Immediately after learning about the successful landing, did President Obama congratulate NASA and its engineers? After all, this President has annually made a big deal of his picks in the NCAA basketball tournament. With NASA, well, not to my knowledge. Perhaps he did after a couple of days?

Did Candidate Romney immediately congratulate NASA and its engineers? Not to my knowledge. Perhaps he did after a couple of days?

Will the winning Super Bowl team be invited to pose with the President at the White House? You betcha! Because, "the ability to run faster or throw farther than other people is a

contribution to the common good" more than, for instance, the NASA engineers' contribution to the common good? And then we wonder why kids in America don't feel inclined to work on their math and science skills? Oh well!

1 comment:

Ha Ha - you have to be enchanted by sport to understand this my friend. You are made differently - that's all :):)

Post a Comment