As a colonizer-hating pinkie, I was against Thatcher and the UK, even if I had no idea about the issues. Much later in my life, when I watched Groucho Marx, I wished I had known about "I'm against it!" as my guiding principle ;)

When I did find out from the atlas where the Falklands are, it shocked me that the UK would go to war so far away from home over some small islands.

The Falklands are practically a launching pad to the Antarctic and with barely any population, yet Thatcher was keen on fighting for it!

A year later, Reagan sent the US forces to invade Grenada. Some simpaticos they were!

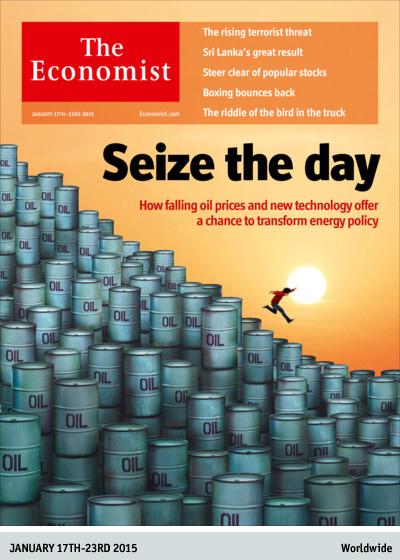

A few weeks ago, Larissa MacFarquhar wrote about how much the Falklands have transformed over the past couple of decades and are now at global crossroads. A recent development there was about oil:

Since the nineteen-nineties, oil companies had been exploring the waters around the islands, and by the early twenty-tens it had become clear that substantial oil deposits existed in the basins offshore.Money started coming in.

Well, all that was in an era before COVID-19. Once the coronavirus took charge of the world, everything changed.

In late March, as the plague drew closer, and the planes stopped coming, the islanders, like people everywhere, sat at home and went online, trying to figure out what was going to happen. Oil prices had plunged since the pandemic began, and covid had been spreading among workers living in close quarters on rigs, so it seemed unlikely that drilling would start anytime soon. With restaurants closing in Europe, demand for fish was a fraction of what it had been, and that was in addition to the possibility that Brexit would result in European tariffs approaching twenty per cent. It was not yet clear what all this meant for the fisheries, but their revenues made up nearly two-thirds of the islands’ income, so any reduction would have an enormous impact. Tourism was the second-largest business, and that consisted almost entirely of cruise-ship passengers. Who was going to sign up for a cruise now? And if the tourists stopped coming restaurants and hotels would close. You weren’t allowed to stay in the Falklands without a job, so the people who worked there and didn’t yet have permanent residency might have to go home.And what happens to the offshore oil exploration? A gambler's loss:; "tapping some fields no longer makes economic sense"

What would happen if planes stopped bringing in regular supplies? Would the islands become remote once more, hoping the deliveries came in, relying on homegrown food if they didn’t? In the old days, fruit was shipped in once a month—it was hard to grow anything on the islands other than berries—and people called mutton “365” because they ate it every day, sometimes for all three meals. Could that happen again? Would younger people who’d grown up in Stanley learn to slaughter sheep?

[A] decade after the discovery of as much as 1.7 billion barrels of crude in surrounding waters, the British overseas territory known for sheep rearing and tension with Argentina looks as remote as ever. Rather than the next frontier, the project to extract energy risks being added to a list of what companies call “stranded assets” that could cost them huge sums to mothball.The coronavirus has, in some ways, accelerated the shift away from fossil fuels, even as the sociopath in the White House continues to operate in his own world of alternative facts. A tRumpian world in which coal is king, and oil is black gold.

I wonder if the stable genius knows where the Falklands are!