Within a few semesters in graduate school, and prior to formally becoming a PhD candidate, I reached a firm conclusion. Two conclusions, actually.

The first was simply that experts already knew plenty about many collective problems and the needed public policy responses to them. Global warming, for instance, is, for all practical purposes, an old topic about which experts knew what to do even back in the 1980s.

The second conclusion was about democracy. As warped and inefficient as democracy is, it is far better than other systems that we have tried. However, the public, who are the ones that make democracy possible, was not aware of what experts knew, and experts weren't conversing with the public. Politicians talked with the public and, unfortunately, said whatever they wanted to in order to win votes and be in power.

I decided that I would write for the public. I felt the urgency to make the public aware of our common issues and how to think about them, and lost any interest in writing academic papers that even academics would not read.

Towards the end of graduate school, I started contributing commentaries to local newspapers. I wished that one of the papers would just make me one of their columnists, even if they didn't pay me a penny.

In the commentaries that I wrote, I thought long and hard about connecting the big picture to the local dynamic. "Will it play in Peoria?" as they say in journalism. And, of course, the issues had to be timely. The commentaries that were published were not out of the blue and on whatever topic that I liked. The commentaries had real contexts in the real world.

An example is

this column that was published in July 2012, in which I appreciated the Americans with Disabilities Act. The anniversary of that legislation was coming up and I timed my column for that. It was published on July 20, 2012, in time for the anniversary date of July 26th when the law became effective.

I wrote in that piece:

The ADA is also a wonderful example of why we need government, and how political parties can work constructively toward the betterment of the people — a concept that has become old-fashioned and is drowned out increasingly by the loud and harsh yelling that accompanies the trivial pursuits played by politicians and commentators.

In 2012, I, like the rest, had no idea that

tRump would get elected to the Oval Office four years later, and that the dysfunctional politics of 2012 that I was complaining about would come across as noble and saintly discussions!

I hope against hope that the elections this upcoming November, which will be after the January 6 Committee publishes its report, will get us back to doing the best work for the greater good of the country and the world.

The following is the column from 2012:

*************************************

The Register-Guard (July 20, 2012)

The United States’ current

dysfunctional politics reminds me of the contrast with a serious piece

of history-making legislation: the Americans with Disabilities Act,

which was signed into law in July 1990.

I was in graduate school in Los Angeles

and in the early phase of getting to know the new country when the ADA

was introduced in Congress. The idea of the act appealed to me as noble:

that people with disabilities ought to be accommodated so that they,

too, can rise to their potential and freely engage in the pursuit of

happiness.

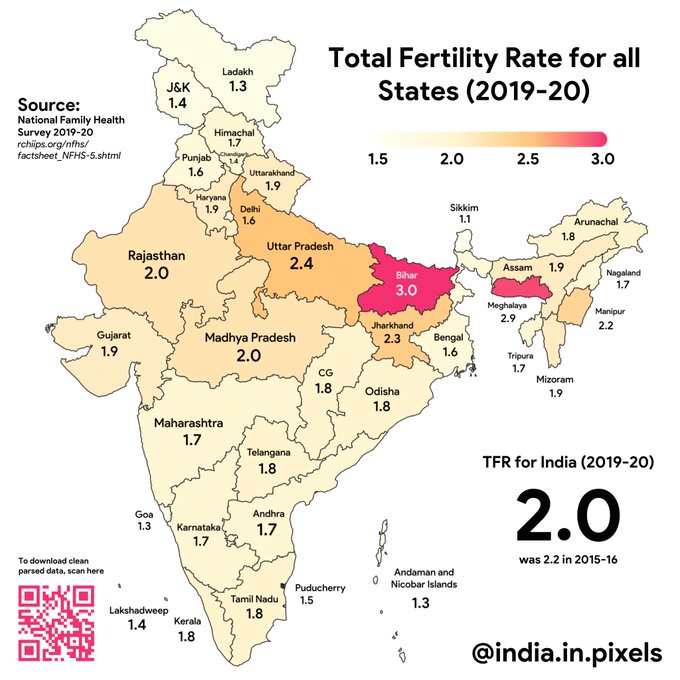

Having grown up in India, I had witnessed

at close quarters many different ways in which friends and relatives

were restricted, sometimes literally to within their homes, because of

disabilities. A distant uncle, for instance, who lost his eyesight as a

young adult became practically unwanted in his own family because he had

become a “burden.” India’s public spaces are daily reminders of the

extreme challenges in everyday life for those who lack full physical

abilities.

If a great society is identifiable by how

it takes care of those with limitations of any kind, then the unfolding

of the ADA — from the introduction of the bill to its implementation,

which continues — has been a story about which we truly can be proud.

The ADA was not without its opponents.

While it was an academic exercise for me to learn in coursework about

how cost-benefit analysis is employed in public policymaking, it sounded

quite awful when critics argued that the ADA would increase costs.

Claims that the law would become a mandate conveniently overlooked the

reality that those with disabilities were being treated as less than

equals. When religious institutions were concerned that they would be

forced to accommodate disabled people by spending money on structural

changes to their buildings, I was struck by how much they seemed to be

going against their own fundamental teachings on how human beings should

be treated.

The bill eventually passed and became the

law of the land, despite a divided government then — the U.S. Senate and

the House were in the control of the Democratic Party, and a Republican

president, George H.W. Bush, was in the White House. The final passage

of the bill was, for all purposes, completely and totally bipartisan — a

world away from the contemporary bickering over all things trivial!

The implementation phase of the ADA

coincided with my first few years of gainful employment. In the small

public agency that I worked for, we now had an additional responsibility

of conforming to the ADA.

It became even more fascinating as the

Internet gave us all an entirely new way to deal with information, which

required us to think about accommodating those who were challenged

visually. Later, when I returned to the academic world, I was impressed

with how the ADA translated to accommodating students constrained by

their hearing disabilities.

The ADA-led accommodations have become so

much a part of my existence here in the United States that I forget how

different conditions are elsewhere — until I cross our borders, that is.

My recent experiences in different parts of the world were reminders of

the phenomenal advances in the United States on this front.

Accommodating the disabled has required us

to spend on everything from sidewalk improvements to sign language

interpreters. These are additional expenses, yes, when compared to how

we conducted our affairs before 1990. But I bet there are very few

people in this country anymore who would ever question these kinds of

“expenses,” because we fully understand the value these deliver — a

value that cannot be captured through any bean counting or cost-benefit

analysis.

The ADA is also a wonderful example of why

we need government, and how political parties can work constructively

toward the betterment of the people — a concept that has become

old-fashioned and is drowned out increasingly by the loud and harsh

yelling that accompanies the trivial pursuits played by politicians and

commentators.

.jpg)