In a letter posted on the college's web site a few days before the event, Western President John Minahan notified students that the display would be on campus and that it complied with university and City of Monmouth scheduling requirements.I stayed away from the protest, consistent with my own way of being a politically active faculty who doesn't abuse the privilege that I have been given, but did observe it--I am a curious person, and an engaged citizen! (For the record, I believe abortion is murder, until and unless we figure out how to create life outside the womb. But, that does not make abortion illegal--I believe it is a pregnant mother's right to terminate the pregnancy. Yep, the sperm donor has no say in it.)

Minahan wrote that the presence of the project "represents an opportunity to test our commitment to respect the (free speech) rights of others and the challenge to use that respect to temper our individual response to potentially controversial material."

Students need to think, organize, articulate, and act on their beliefs and understanding of the world, and our job is to help them understand only within the context of the classes we teach. If they invite us to an extracurricular thinking, and if we want to help out, fine. But, we have no business otherwise. Leaving students alone is the best approach also because then we do not have to figure out where and how we can or should support any of their causes.

But, of course, the university and its faculty don't think that will serve the university and its faculty well.

The latest in this: first an email from the president (this is not the same as the one from the abortion story):

All WOU students, faculty and staff: On Thursday, April 25, the Oregon Student Association and the Oregon Community College Association will be holding a day at the Capitol to support higher education and help educate legislators on relevant issues. The purpose includes statewide advocacy for higher education funding and need based student aid. A delegation of students from Western is being sponsored by the Associated Students of Western Oregon University (ASWOU). ASWOU has asked me to endorse student participation at this event and I do, wholeheartedly. I encourage students to attend as much of the day that they can and let their voices be heard. All student attendees must make appropriate prior arrangements directly with their professors and instructors for making up assignments and other course related requirements. Faculty are encouraged to accommodate the reasonable requests of students that desire to participate in this worthwhile activity. Sincerely,Mark Weiss, WOU PresidentBut, April 25th is not a weekend--we have classes that Thursday, including mine. Students and taxpayers together pay significant amounts to make those classes possible. Yet, we would want students to ditch classes, wasting the money invested, and spend time chanting slogans at the steps of the capitol?

And then came another email--from the president of the faculty union (full disclosure: I am not a member of the union):

Dear Colleagues,So, the president says that it is ok if students want to ditch classes and head to Salem. The faculty leader takes it "one step further" and urges us to accommodate this. (BTW, notice the signing off: "In solidarity" ... yes, comrades!)

As some of you know, I have enjoyed the privilege of serving on the State Board of Higher Education for the past year and a half. At each board meeting, the president of the Oregon Student Association delivers a presentation about OSA's impressive work on behalf of students in our state. This year, OSA has organized a statewide lobby day and informational rally at the Capitol for college students on Thursday, April 25. You recently saw a message from President Weiss encouraging your support of student involvement in the Lobby Day. I would like to take his message one step further by urging you to make accommodations for students missing class in order to participate in this civic engagement opportunity. Student voices make a significant impact on our legislators and their decisions and, as we all know, higher education needs all the help it can get from the Capitol.

Thank you for considering this request from a colleague and for helping students learn the value of civic engagement and advocacy for the issues that matter most to them.

In solidarity,

Emily

Emily Plec

Professor

The faculty leader says there that it is to help "students learn the value of civic engagement and advocacy for the issues that matter most to them." Hmmm .... so, why then did they feel the need to counter the pro-life rally? Shouldn't they have equally urged us to help students with advocating for issues that matter most to them? Or should we help students advocate only for issues that matter most to us and not to them?

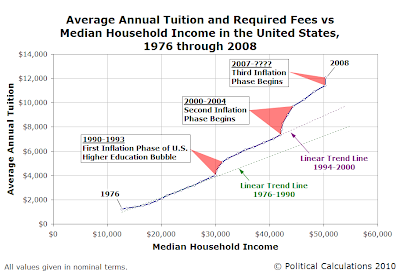

Of course, this time students engaging in the political process is in the interest of the faculty and the university--students are being used to press the legislature for more funding, so that we can continue to do higher education the way we do, even though it is screwing up students' lives. After all, "institutions will try to preserve the problems to which they are a solution."

If only students would critically think about all these issues, they will soon figure out there is something rotten for them when the institution and faculty are urging them to lobby for a "greater cause." In fact, maybe students ought to be like the typical fourteen-year old who does exactly the opposite of what the parents would want the teenager to do. Here, if the university and faculty want students to go to to Salem and lobby for more funding, then that is the last thing they should think of doing ;)