"Call me Ishmael."

"Mother died today."

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

And then there is the lengthy paragraph that begins Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way--in short, the period was so far like the present period that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

To those memorable lines (and more) I will boldly add this one too:

The present, we assume, is eternally before us, one of the few things in life from which we cannot be parted.

What a powerful and profound thought!

The paragraph-sentence that follows adds more:

It overwhelms us in the painful first moments of entry into the world, when it is still too new to be managed or negotiated, remains by our side during childhood and adolescence, in those years before the weight of memory and expectation, and so it is sad and a little unsettling to see that we become, as we grow older, much less capable of touching, grazing, or even glimpsing it, that the closest we seem to get to the present are those brief moments we stop to consider the spaces our bodies are occupying, the intimate warmth of the sheets in which we wake, the scratched surface of the window on a train taking us somewhere else, as if the only way we can hold time still is by trying physically to prevent the objects around us from moving.

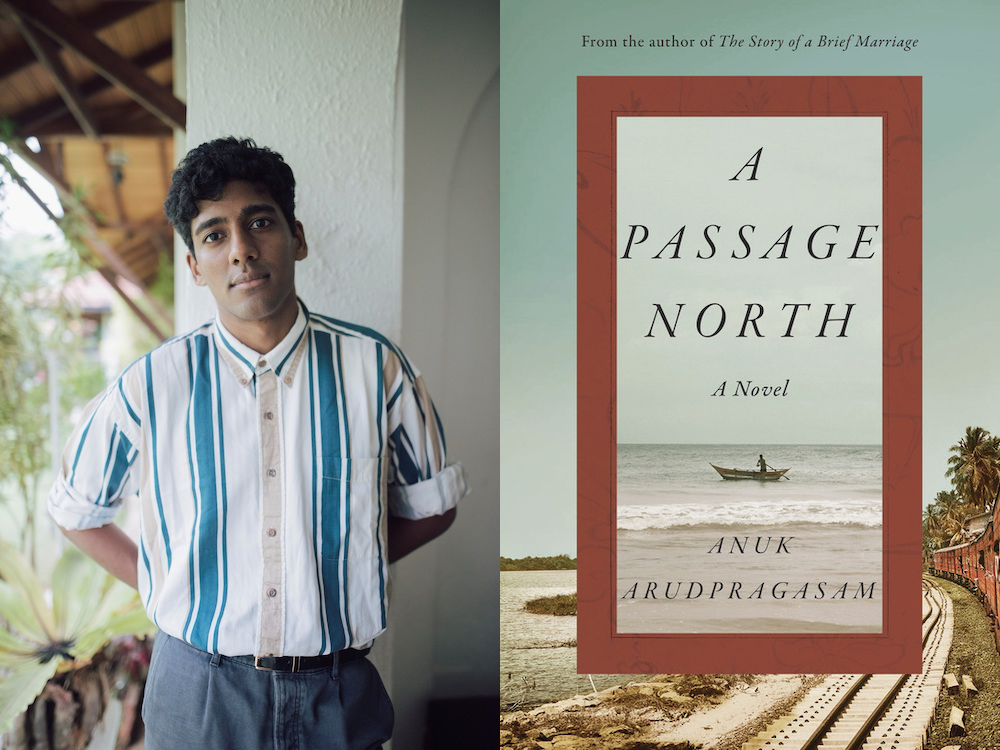

The author gets the reader ready for an intensely retrospective, reflective narrative. Anuk Arudpragasam has me wanting more right from those opening pages of his A Passage North.

When I first came across that name a few weeks ago, when I added the book to my reading list, I felt that the author either was a Sri Lankan Tamil, or a descendant of a Tamil who had ventured, on their own or as indentured labor, into a land far away like South Africa or Trinidad. In both, the Tamil Hindu names are spelled differently from how they are back in the old country. Like how the name Nagamuthu of the old country gets spelled as Nagamootoo.

Arudpragasam is, similarly, a differently spelled Arulprakasam of the old country. And, yes, he is from Sri Lanka.

Arudpragasam wrote the novel when he was wrapping up his PhD in philosophy at Columbia University! Maybe that explains the weighty opening sentence?

I didn’t come from a book-reading household, so my entry into books was arbitrary. It happened to be through philosophy books that I found at a bookshop close to my house. The first book I read was Plato’s Republic. Then it was Descartes’s Meditations and a book of lecture notes of Wittgenstein’s called The Blue Book. I tried to read Aristotle’s Ethics, but I stopped that after a while. I read a lot of philosophy when I was fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, before I went to university. That was my entry into literature—I only really started reading fiction when I was in college. There was one book in particular, The Man without Qualities, by Robert Musil—he actually had a Ph.D. in philosophy. He has these long, digressive, essayistic sections in his book, which I haven’t read since I was twenty, so I don’t know how I’d feel about it now. At the time I was very moved by the way he places philosophical questioning and response in a kind of living, bodily situation. Philosophical problems arise in lived context, in response to real situations, and in philosophy, academically, you don’t really ask or answer questions in that way. But I read that book, and it showed me that there was a place in fiction and novels for a lot of what interested me about philosophy. Actually placing these things in their lived context charges philosophy in a way that simply discussing them abstractly does not. So I read that book, and I decided that I would like to write fiction, that I wanted to be the kind of person who could write a book like that.

It is not that difficult, however, to imagine PhDs writing fiction. There are at least four that I can name without checking with Google, and whose works I have blogged about: Jhumpa Lahiri, Kim Stanley Robinson, and Alan Lightman. S.J. Sindu was a recent addition to that list.

I am, yet again, reminded of Orhan Pamuk's observation on the (coming) dominance of non-white writers.

No comments:

Post a Comment