International travel has been upended in this COVID-19 context. The Indian government has even

suspended all visas for foreigners, which means that I cannot even go to the old country for a while. In reality, we have no idea when countries might open up for international travel.

A worry that the son might not be able to come back in time is why

my great-grandmother forbid my grandfather

from taking up a job in Ceylon, as Sri Lanka was then called. (My own interpretation is this is also the larger logic behind the old Hindu tradition's belief that it is a sin to travel over the seas.)

We take for granted that life as we know it will continue forever. Operating in that framework, we even put off visiting with parents.

I blogged about this in July 2013. I wrote there: "I spend money to go to India because, probabilistically speaking, while I have quite a few more years to live, my parents face a much more limited horizon. ... As a confirmed atheist, all I have to figure out is whether I am at peace with the decisions I make. I know I won't be at peace if I didn't make that trip to India"

Over the last 18 years, by my mental count, I have made 19 trips to India. Two of those trips coincided with my sabbaticals, which meant that I spent three months there during each of those sabbaticals, instead of the usual three weeks.

I have no idea when the next trip might be, and who might or might not be around when I get there. Or if there will be another trip at all. Am at peace within, supported by the evidence that I went when I could. As for the future,

que sera sera.

The following is an edited version of that July 2013 post:

************************************

I had a good night sleep after an enjoyable and eventful weekend. I woke up with a clear head, and had coffee and breakfast. I read and blogged. I had a lovely walk by the river before it warmed up. Lunch tasted awesome--the leftovers from the Saturday cooking.

And then I read

this piece at

Slate: It is "a calculator to to tell you how many times you'll see your parents before they die."

Of course I had to read it the moment that kind of a lead popped up. After all, the annual trips to India over the last decade have been exactly for this reason, even though, this travel-dreaming blogger on a limited budget could easily divert that expense in order to go somewhere else. And, boy do I have some travel plans in mind!

I spend money to go to India because, probabilistically speaking, while I have quite a few more years to live, my parents face a much more limited horizon. In fact, it is even probable that

they are into overtime.

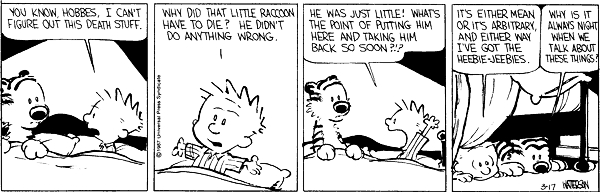

Death is guaranteed right at conception. It is only a matter of when. My first lesson on my own mortality was

when I was way young. It is not that I sit around waiting for my own death or anybody else's; it is merely a realization that one day it will happen.

As an atheist, I am not buying my ticket to heaven by visiting with parents, nor do I have to worry about spending eternity in hell if don't spend that time with them.

As a confirmed atheist, all I have to figure out is whether I am at peace with the decisions I make. I know I won't be at peace if I didn't make that trip to India and, instead, if I spent those weeks in, say,

Argentina that I have been drooling to go for years. Further, it is not that visiting with the parents is a pain--it is always a pleasure. And I will get to meet with a few friends and relatives.

Hence, I go. And, yes, I am all set with the air tickets for the upcoming annual trip, later this year.

So, I did click on the link to the site that does the calculation. A site whose address says it all:

seeyourfolks.com

As the

Slate article pointed out, the site's simple interface was inviting. I punched in the data. The site had this to report:

Not a surprise to me--it matches my understanding of life expectancy at birth.

So, why create such a site?

We believe that increasing awareness of death can help us to make the most of our lives. The right kind of reminders can help us to focus on what matters, and perhaps make us better people.

Exactly! This has always been my understanding of life, and death too.

When we realize there is only a limited amount of time, we are then able to easily rank some as important and others are not worth even a tiny second of our lives.

If the latter, we stop caring for sports in which people

get paid gazillions to entertain us. We stop caring for movies that are

formulaic. We don't care for

unprofessional colleagues. We end marriages and we divorce. Life is way too short for these.

I would rather spend time, and money, on

what truly matters. I prefer humans who are genuinely happy to give me a minute or more of their lives. I travel to visit with

my love. I visit with my parents. I read. I think. I help students think. I share ideas with people. I walk by the timeless river.

I blog about all these.

This is all that matters.

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4281575/abolished.png)